Dragonflies embody the spirit of summer – these big, beautiful insects are some of the showiest to be found in the UK and watching them patrol along the water is a seasonal delight to be savoured every year.

Damselflies, the wafting relative of the dragonfly, flutter delicately around the water margins, in counterpoint to the direct, rapid flight of dragonflies.

Where dragonflies are robust and speedy, damselflies are small and weak-flying. Since dragonflies are formidable and opportunistic aerial predators, damselflies often fall prey to them, alongside all manner of insects, from midges and mosquitoes to butterflies and moths.

Typically, dragonflies eat on the wing, discarding inedible wings and chitin as they go. If you find a scattering of these parts across a path, it’s a good sign that you’re in a dragonfly hunting territory.

From the earliest emergences in April to the final flights at the end of September, BBOWT conducts dragonfly surveys to monitor populations at our nature reserves. By gathering this data, we can ensure that our habitat management is effective and that populations of some of the region’s rarest species will continue to thrive.

Dragonfly transects are surveyed once a week from the end of April to the end of September. In order to ensure that the records can be compared between years, the methodology and transect routes must be consistent.

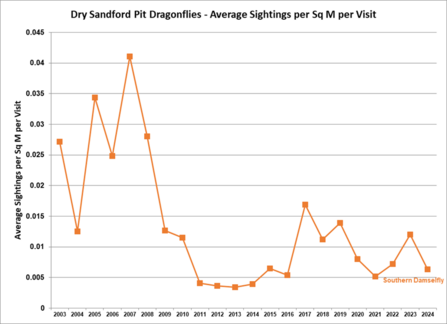

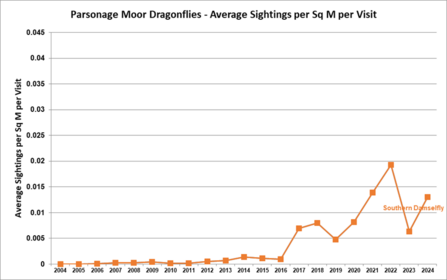

I cover two transects in the beautiful Cothill village, at Dry Sandford Pit (shown in the photograph above) and Parsonage Moor (below). One of the perks of dragonfly surveys is that the weather must be warm and dry – any sign of rain or high winds, and dragonflies will seek shelter in vegetation, making them nearly impossible to spot. For this reason, it is a requirement that there should be at least 50% sunshine, and a temperature above 17°C. If the weather isn’t good enough, the survey can’t go ahead.