A former chalk quarry, College Lake is now one of BBOWT's flagship nature reserves. Read about the site's industrial heritage, geology and fossil finds.

Author: Neil F. Adams, Curator, Fossil Mammals, Natural History Museum, London.

Industrial heritage

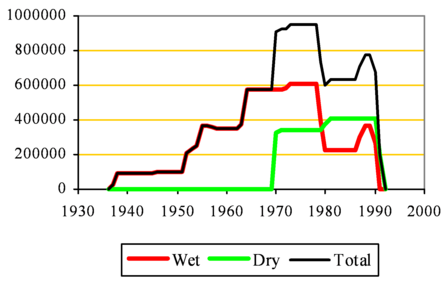

The Tunnel Portland Cement Company began quarrying chalk at the Pitstone Quarry site in 1937. Each year it produced roughly 100,000 tonnes of cement, which required about 190,000 tonnes of chalk. In 1968, Tunnel Portland Cement Company became Tunnel Cement. Production peaked at ~950,000 tonnes per year in the early- to mid-1970s. Later in 1986, Tunnel Cement was re-branded as Castle Cement after merging with several other cement companies. Castle Cement continued quarrying at the site until 1991.

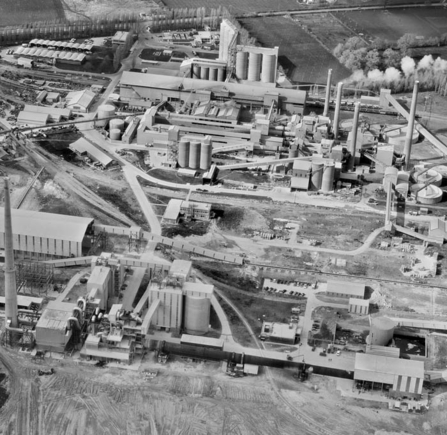

© Historic England

The cement works at Pitstone Quarry in April 1972, showing the newly constructed 'kiln 5' in the foreground.

Annual cement production at Pitstone Quarry in tonnes per year during the 1900's.

College Lake Nature Reserve is what is left of Quarry 3, where quarrying began in 1969. During quarrying of the chalk in this area of the site, quarry workers came across some very different rocks and sediments cut into the chalk. These were ice age (Pleistocene) river channels, which contained many large fossils, and periglacial slope deposits.

The site was designated a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) in 1976 for these ice age river channel and slope deposits, as well as the fossils they contained. Because the planning permissions for the quarry had been granted before the site received protected status, quarrying was allowed to continue. Nevertheless, a collaboration between English Nature (now Natural England) and the Tunnel Portland Cement Company ensured some of the scientifically important, fossil-rich channel was conserved as a promontory (the Mammoth Promontory) that would not be quarried.

Thanks to the efforts of Graham Atkins, a former lorry driver at the cement works, the quarry manager was persuaded that Quarry 3 could be restored in a more environmentally friendly way by creating a nature reserve. This eventually led to the development of College Lake Nature Reserve. Originally, Quarry 3 was destined to be restored to agricultural land after quarrying operations had finished. With a small team of volunteers, Graham worked with George Goddard (former general manager of Castle Cement) to transform the quarry. Graham wrote a book entitled ‘Creating a Nature Reserve: The Story of College Lake’ that was published in 2013 about the site’s journey from quarry to nature reserve. The site is now managed by BBOWT and contains diverse habitats including the lakes, woodland and chalk grassland.

College Lake history: Graham Atkins (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ArOkulyhY6s)

How a former chalk quarry became a nature reserve through the vision and efforts of Graham Atkins and a band of dedicated volunteers.

Geological story

The chalk

The oldest rocks exposed at College Lake Nature Reserve date to the Cretaceous, when dinosaurs dominated life on land. The Cretaceous rocks at College Lake are around 100–95 million years old from a period in the Late Cretaceous known as the Cenomanian. During the Cenomanian, large parts of the UK were covered by a relatively shallow ocean, including the area that is now College Lake. The Cenomanian rocks in the nature reserve are chalks. These rocks are soft and greyish and, fittingly, they belong to the Grey Chalk Subgroup – a large group of rocks that can be identified across the country.

The oldest chalks, found at the bottom of the old quarry, belong to the West Melbury Marly Chalk Formation, and above these are somewhat purer, whiter chalks belonging to the Zig-Zag Chalk Formation. The lower rocks are called ‘marly’ chalks because they contain more clay, which gives them their characteristic grey colour. These clays were probably washed into the sea from the nearby land. As sea level rose in the Cenomanian, the distance to the nearest land increased. Less clay reached the area, so the chalks of the Zig-Zag Chalk are purer and contain more calcium carbonate. The calcium carbonate in the chalk derives from the hard skeletons of various types of tiny plankton that once lived in the ocean.

Fossils have been found from the chalk, particularly from the marly chalks that were deposited in shallower seas. The fossils include remains of sea creatures such as ammonites, sea urchins, sea lilies, starfish, bivalves (a group including clams, oysters, and mussels), crustaceans (including lobsters and crabs), sea snails, sponges, and sharks. Some plant material, probably washed into the sea from the nearby land, can also be found as pieces of driftwood and as associated small fragments.

The Ice Age

On top of the chalk around College Lake are sediments that date to the Pleistocene (also known as the Ice Age). The Ice Age began around 2.5 million years ago and ended when the current warm period that we still live in began 11,700 years ago. During the Ice Age, there were repeated shifts in climate between cold periods (known as ‘glacials’) and warm periods (known as ‘interglacials’). These shifts were caused by cycles in the Earth’s orbit. Glacials occurred when the Earth was furthest from the Sun and received least solar energy. Interglacials occurred when the Earth was closest to the Sun and received most solar energy.

The Anglian glaciation

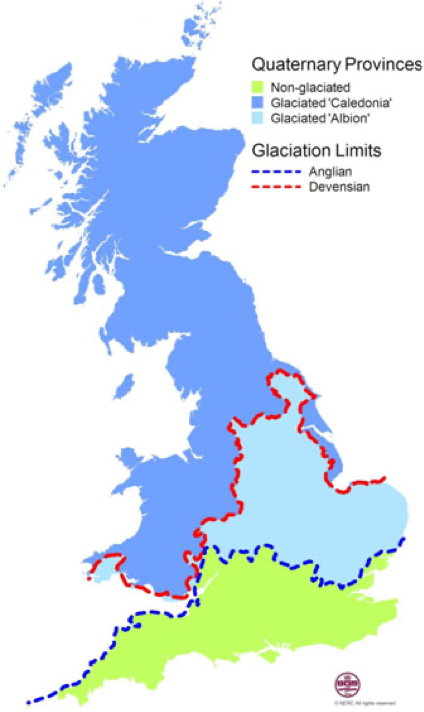

The most severe glacial period of the Ice Age (the ‘Anglian’ glaciation) occurred in Britain around 450,000 years ago. A thick ice sheet covered much of the UK during this time and extended far to the south (see blue dashed line on image below). It is now thought that the margin of this ice sheet was only tens of kilometres to the north of College Lake. The ice sheet transported rocks and sediment from hundreds of miles away into the Vale of Aylesbury.

© British Geological Survey

The reconstructed limits of ice sheets across Great Britain during the Anglian period (450,000 years ago) and during the last glacial period, the Devensian (25,000 years ago).

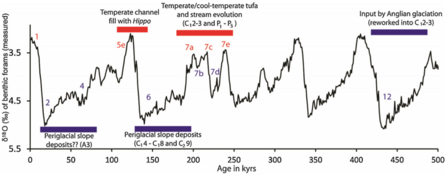

A climate curve showing the shifts between glacial periods (troughs) and interglacial periods (peaks) during the Ice Age, annotated with events that occurred at the site that is now Pitstone Quarry SSSI and College Lake Nature Reserve (source: Murton et al., 2015).

The far-travelled rocks and sediments transported by the Anglian ice sheet can be found in several river channel deposits that were discovered in the Pitstone Quarry during the 1970s. These channels had cut into the underlying chalk and had deposited the sands and gravels flowing through them.

Fossil finds

A series of infilled river channels are preserved in the Pitstone Quarry SSSI and are believed to date to a warm interglacial period 200,000 to 250,000 years ago.

At the start of this warm period, springs developed near the foot of the Chiltern Hills. These springs deposited tufa – a type of limestone that forms when carbonate minerals precipitate out of water.

Excavations through the river sediments recovered nearly 12,000 fossils, including bones and teeth of many different animals. Fossils of plants, slugs and snails, beetles and other invertebrates have also been found. All these fossilised animals and plants allow a detailed insight into the environment at College Lake around 200,000 years ago.

Mammals

Mammal fossils include:

- Eurasian water shrew (Neomys fodiens)

- Hare or rabbit (indeterminate Leporidae)

- European water vole (Arvicola terrestris cantiana)

- Northern vole (Microtus oeconomus)

- Vole (Microtus sp.)

- Lion (Panthera leo)

- Brown bear (Ursus arctos)

- Red fox (Vulpes vulpes)

- Grey wolf (Canis lupus)

- Woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius)

- Straight-tusked elephant (Palaeoloxodon antiquus)

- Wild horse (Equus ferus)

- Red deer (Cervus cf. elaphus)

- Aurochs (Bos primigenius)

- Steppe bison (cf. Bison priscus)

The mammals, particularly horse and mammoth, suggest an open grassland habitat, and the northern vole is found in wet, grassy habitats today. Water vole and water shrew suggest slow-flowing water. Woodland habitats are inferred from straight-tusked elephant, aurochs and brown bear, and warm conditions are inferred from presence of straight-tusked elephant and aurochs.

Plants

The following plant species were recovered as macrofossils:

- Greater chickweed (Stellaria cf. neglecta)

- Sweet violet (Viola odorata)

These two species are indicative of shady patches.

- Mouse-ear chickweed (Cerastium cf. fontanum)

- Common whitlowgrass (Draba verna)

- Fumewort (Fumaria sp.)

- Common knotgrass (Polygonum aviculare)

- Spring cinquefoil (Potentilla tabernaemontani)

- Dandelions (Taraxacum sp.)

- Chickweed (Stellaria cf. media)

These seven species are indicative of grassland, open and disturbed ground.

- Water-starwort (Callitriche sp.)

- Long-stalked yellow-sedge (Carex cf. lepidocarpa)

- Watercress (Nasturtium officinale)

- Horned pondweed (Zannichellia palustris)

These four species are indicative of waterside, damp ground and shallow water.

The following plant species were found in the sediments of the lower channel as microfossils of pollen and spores:

- Tree pollen is quite rare in the lower channel deposits, but pollen from pine trees (Pinus) is most common. Pollen from spruce (Picea), alder (Alnus), lime trees (Tilia), poplar (Populus), oak (Quercus) and elm (Ulmus) was also found.

- Among shrubs, pollen of juniper (Juniperus), redcurrant (Ribes rubrum) and hazel (Corylus) were found.

- Herbs dominate the pollen assemblage, including grasses (Gramineae), sedges (Cyperaceae), chicory (Cichorium intybus), germanders (Teucrium), plantains (Plantago), buttercups (Ranunculus), figworts (Scrophularia), hogweed (Heracleum) and water dropworts (Oenanthe).

- Pollen of aquatic plants was also discovered including of water-starworts (Callitriche), mare’s-tail (Hippuris vulgaris), common frogbit (Hydrocharis morsus-ranae) and horned pondweed (Zannichellia palustris).

- Among spore-producing plants, such as ferns, the spores of the following species were discovered: moonwort (Botrychium lunaria), marsh clubmoss (Lycopodiella inundata) and the marsh fern (Thelypteris palustris).

The plants suggest there was a shallow, still or slow-moving channel, fringed by wetlands and marsh vegetation. In drier areas, herb-rich calcareous grassland dominated with some open, stony ground and steep slopes. Disturbed sandy and gravelly areas existed around the channel sides, probably caused by trampling of large mammals coming to drink and wallow. Trees probably grew singly or in small clumps of open woodland on the channel sides.

Molluscs

The following species of molluscs were recovered:

- Dwarf pond snail (Galba truncatula)

- Amber snails (indeterminate Succineidae)

- Hairy snail (Trochulus hispidus)

- European fingernail clam (Sphaerium corneum)

- Lake orb mussel (Musculium lacustre)

These five species indicate marsh and aquatic, but also grassland, conditions.

- Three-toothed moss snail (Azeca goodalli)

- Moss chrysalis snail (Pupilla muscorum)

- Slugs (Limax sp.)

- Two-toothed door snail (Clausilia bidentata)

- Copse snail (Arianta arbustorum)

These five species indicate dominance of grassland with shady patches. These species include some southern species that indicate a warm climate.

Beetles

92 taxa of beetles were recognised.

The presence of the leaf beetle Donacia semicuprea and the marsh weevil Notaris acridulus suggest a marshy habitat with aquatic grasses growing within and beside the channel. The dung beetle Aphodius and the spiny-legged rove beetle Oxytelus gibbulus are associated with dung that may have been produced by large herbivores near the channel. The ground beetle Agonum thoreyi lives on the margins of pond with reedy vegetation. Several other marsh-loving beetle species were also discovered (the leaf beetles Hydrothassa hannoveriana and Prasocuris phellandrii).

In places, the swampy vegetation was more open with bare patches of soils and tall plants, habitats suitable for the ground beetles Elaphrus cupreus and Loricera pilicornis. The ground beetle Clivina fossor prefers open grassy habitats with short, patchy vegetation. Several other species from the ground beetle family (the Carabidae) suggest open, meadow-like country with rich soil and weedy vegetation.

The beetles discovered suggest trees were sparse or relatively far from the channel, since no tree-dependent species were found.

Ostracods

11 species of ostracods were recovered from the lower channel sediments. The ostracod species suggest there was year-round streamflow, with aquatic vegetation in the chalk stream. Some of the species (e.g. Candona neglecta and Herpetocypris reptans) prefer temperatures similar to the site today, with soft sediment for burrowing. Some species (e.g. Potamocypris wolfi and Cypridopsis subterranea) are also associated with calcareous springs.

Human fossils and archaeology

There have not been any published human fossils or archaeological artefacts from the lower channel deposits in Pitstone Quarry SSSI. However, there are at least fourteen archaeological sites known across south-east Britain that date to the same warm interglacial as recorded in the lower channel. Pontnewydd Cave in Wales records the only human fossils from this period: seventeen teeth and a jaw fragment that are attributed to Neanderthals. Although it is not dated with certainty, the type of archaeology (Levallois technology with handaxes) from a site near Caddington in the Chilterns is consistent with this interval. Caddington is only around ten miles from College Lake and other better-dated sites with similar archaeology in the Thames catchment are not far either.

It is very likely that humans (probably Neanderthals) were active in Britain at the time the lower channel sediments were being deposited. They may have been active in the area of College Lake and not left a trace (or they left a trace that has not yet been discovered). Alternatively, they may have been focused in others parts of the country at that time (archaeological sites suggest the Thames and its tributaries were used more than other areas).

The 150,000-year-old glacial period

After the lower channel sediments were deposited, the climate cooled dramatically into the next glacial period. Another ice sheet developed across Britain during this time, but was located much further north than the Anglian ice sheet.

At this time, around 150,000 years ago, periglacial processes were affecting the area around College Lake. The intense cold froze and cracked the chalk bedrock (by a process known as thermal contraction) and strong winds deposited wind-blown sand across the region. The broken chalk and other pre-existing sediments slumped off the Chiltern Hills as mass movement deposits (known as ‘coombe rock’). These coombe rock deposits can be found across the College Lake site.

Rivers, fuelled by seasonal snowmelt, eroded and reworked existing sediments into sand and gravel channel deposits. In some of the deposits, infilled ‘ice-wedge’ casts can be found. These wedges formed by the thermal contraction and cracking of the ground. Water infilled the cracks and upon freezing the water expanded, widening them. This process could repeat itself many times, enlarging the size of ice wedges to many metres. Upon melting, sediment could infill the voids that were previously filled with ice, leaving behind a wedge infill or cast.

Although few fossils have been found in deposits of this glacial period at the site, a number of mammal fossils were discovered, including:

- Red fox (Vulpes vulpes)

- Grey wolf (Canis lupus)

- Woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius)

- Wild horse (Equus ferus), a small-bodied form

- Wild cattle (Bos or Bison)

A reduced body size appears to be a characteristic of horses from this cold period across the UK. Small-bodied horses of this age are also known from Somerset, Sussex, and Wales. The decrease in body size has been suggested to reflect the adaptation of horses to stressful climatic and vegetation conditions during this cold, glacial period.

The following plant species were also recovered from sediments immediately above the lower channel as microfossils of pollen and spores:

- Lesser clubmoss (Selaginella selaginoides)

- Common clubmoss (Lycopodium clavatum)

These plants may reflect the cold climate that prevailed after the deposition of the lower channel. Today both clubmosses are found in mainly mountainous regions of northern Europe.

When the climate started to warm again, around 130,000 years ago, the permafrost below ground began to melt. This filled the periglacial sediments, including the coombe rock, with water. There is a difference in density between (1) the coombe rock and (2) the sands and other sediments above it. When the coombe rock became wet and saturated with meltwater, the heavier, denser sands were able to sink into the finer-grained, less dense coombe rock, while the coombe rock was forced upwards into the sands. This process deformed the original layers of sediment, creating warped features known as involutions.

Some potential ways to explain how involutions form include:

- Lava lamps, where the ‘lava’/wax moves around based on differences in densities caused by heating.

- Sinking in quicksand, where a dense object sinks into saturated, wet sand and displaces the sand below, forcing it upwards (perhaps the best analogue for involution formation).

- Feet sinking into mud on wet mudflats (e.g., muddy beaches). When dry, a person can stand on the mud without sinking, but the adding of water (e.g., by incoming tides, etc.) initiates sinking due to density contrasts. Toes sink into the mud and mud is forced up between the toes (similar to sinking in quicksand).

- Something frozen at the base (e.g., ice cream, analogue for permafrost), topped with soft ice cream (e.g., Mr Whippy, analogue for the melted active layer that is like sludge) topped with biscuits which sink into the soft ice cream (analogue for sediment sinking).

- Marble cake – does not imply process, but might be good for visualising the mixing of two different materials, with similar deformation-like structures.

The 125,000-year-old interglacial

What makes the sediments at College Lake unique is that they preserve river deposits from two warm interglacial periods: one around 200,000 years ago and one around 125,000 years ago.

Another river channel, known as the ‘upper channel’ was found cut into the periglacial deposits in an area of Pitstone Quarry that has now been completely excavated away. Because the sediments in this channel were on top of the cold-climate periglacial sediments, they must have been younger and are likely to represent the period of warm interglacial climate 125,000 years ago. A rescue dig through the upper channel was able to recover an important assemblage of fossil mammals, including:

- European water vole (Arvicola terrestris cantiana)

- Straight-tusked elephant (Palaeoloxodon antiquus)

- Narrow-nosed rhinoceros (Stephanorhinus hemitoechus)

- Common hippopotamus (Hippopotamus amphibius)

- Red deer (Cervus elaphus)

- Fallow deer (Dama dama)

- Giant deer (Megaloceros giganteus)

- Steppe bison (Bison priscus)

These mammals suggest warm conditions prevailed, with a mosaic of woodland and grassland habitats. Freshwater aquatic environments are inferred for hippopotamus. The grazing activities of large mammals (hippopotamus, straight-tusked elephant, narrow-nosed rhinoceros) are likely to have maintained much open ground.

The apparent lack of human fossils or archaeology from the upper channel is unsurprising because it is believed that humans were largely or entirely absent from Britain during this interglacial.

Collections – fossils and archives

A relatively small number of mammal fossils from the upper channel (~125,000 years old) is held in the collections of the Natural History Museum in London. The majority of the fossil collections from the site, as well as archive documents, are held in the Bucks County Museum at the Museum Resource Centre in Halton, Buckinghamshire. A collection of fossils from the chalk and ice age deposits are kept on site. The ice age fossils include:

- a bear canine (probably brown bear, Ursus arctos)

- a lion vertebra (probably lion, Panthera leo)

- a horse astragalus and calcaneum (ankle and heel bones), phalanges (toe bones), and teeth (probably wild horse, Equus ferus)

- mammoth molars (probably woolly mammoth, Mammuthus primigenius)

- a wild cattle molar (probably Bos or Bison)

- several smaller ‘carnivore’ teeth (possibly red fox, Vulpes vulpes)

- a possible rhino tooth (possibly narrow-nosed rhinoceros, Stephanorhinus hemitoechus)

- some small mammal remains, including phalanges/toe bones (possibly rabbit/hare, indeterminate Leporidae, or voles, indeterminate Arvicolinae)

These fossils were found during small works on site, e.g. during fence post installation, as well as from washouts and some were found during the original excavations.

Glossary

Calcareous – composed of calcium carbonate (CaCO3); or occurring on rocks rich in calcium carbonate (such as chalk or limestone).

Cenomanian – the oldest stage of the Late Cretaceous, which dates from 100.5 to 93.9 million years ago. It follows the Albian stage of the Early Cretaceous, and is followed by the Turonian stage of the Late Cretaceous.

Chalk – a porous, fine-grained rock, predominantly composed of the calcareous skeletons of microorganisms, including several types of marine plankton called coccolithophores and foraminifera.

Herbs – a seed-bearing plant that does not have a woody stem and dies down to the ground after flowering.

Ice-wedges – tapering, vertically layered piece of ice that extends downwards into the ground often by many metres, resulting from contraction cracks in the ground that form during extreme cold and that fill with water, which expands upon freezing. Often found in river sediments under cold climates.

Involutions – contorted layers of sediment that are often found in areas affected by past or present periglacial conditions; they are thought to result from melting of permafrost. Meltwater fills the sediments with water, and sediment layers of different densities interact with each other and move around. Layers of greater density sink, while layers of lower density rise upwards, leading to contortion and deformation of the original flat, layered structure.

Macrofossils – preserved remains of a once-living organism (fossils) that are visible without use of a microscope.

Microfossils – preserved remains of a once-living organism (fossils) that are not visible without use of a microscope.

Molluscs – soft-bodied, unsegmented animals with a body organised into a muscular foot, a head, and a fleshy mantle that secretes the calcareous shell.

Ostracods – a group of crustaceans that are laterally compressed and enclosed within a bivalved carapace.

Periglacial – a term used to describe an environment where the action of freezing and thawing is currently or was the dominant surface process, often in areas adjacent to glaciers or ice sheets.

Permafrost – permanently frozen ground, where temperatures below 0 °C have persisted for at least two consecutive winters and the intervening summer.

Pleistocene – the first epoch (a type of subdivision of geological time) of the Quaternary time period, which began 2.58 million years ago and ended 11,700 years ago and which is characterised by numerous cycles between glacial (cold) and interglacial (warm) episodes.

Pollen – a powdery substance comprising pollen grains which contain the male reproductive cells of many plants.

Shrubs – a small- to medium-sized woody plant that is perennial (plants that live for more than two years).

Spores – a small, typically one-celled, reproductive unit capable of giving rise to a new individual without sexual fusion.

Springs – a flow of water above ground level that occurs where the water table intercepts the ground surface.

Steppe – a large area of flat unforested grassland.

Tufa – a type of limestone that forms when carbonate mineral precipitate out of ambient temperature water, typically near springs.